The housing crisis or housing affordability crisis is one of if not the most important problem in America and the western world.1 People are struggling to afford to live in the places that they want and need to live in. In 2024, Zillow published a press release claiming that the U.S. housing shortage grew to 4.5 million home. In the same release they explain “This deepening housing deficit is the root cause of the housing affordability crisis.” This is partly due to a fundamental contradiction in the way housing works especially in America. The incentives for both making housing affordable and available as well as ensuring housing is a continuously appreciating asset are at odds. Jerusalem Demsas, a leading voice on the housing crisis writes in The Atlantic a great explanation of this contradiction.

Jerusalem Demsas: The Homeownership Society Was a Mistake

Homeownership works for some because it cannot work for all. If we want to make housing affordable for everyone, then it needs to be cheap and widely available. And if we want that housing to act as a wealth-building vehicle, home values have to increase significantly over time. How do we ensure that housing is both appreciating in value for homeowners but cheap enough for all would-be homeowners to buy in? We can’t.

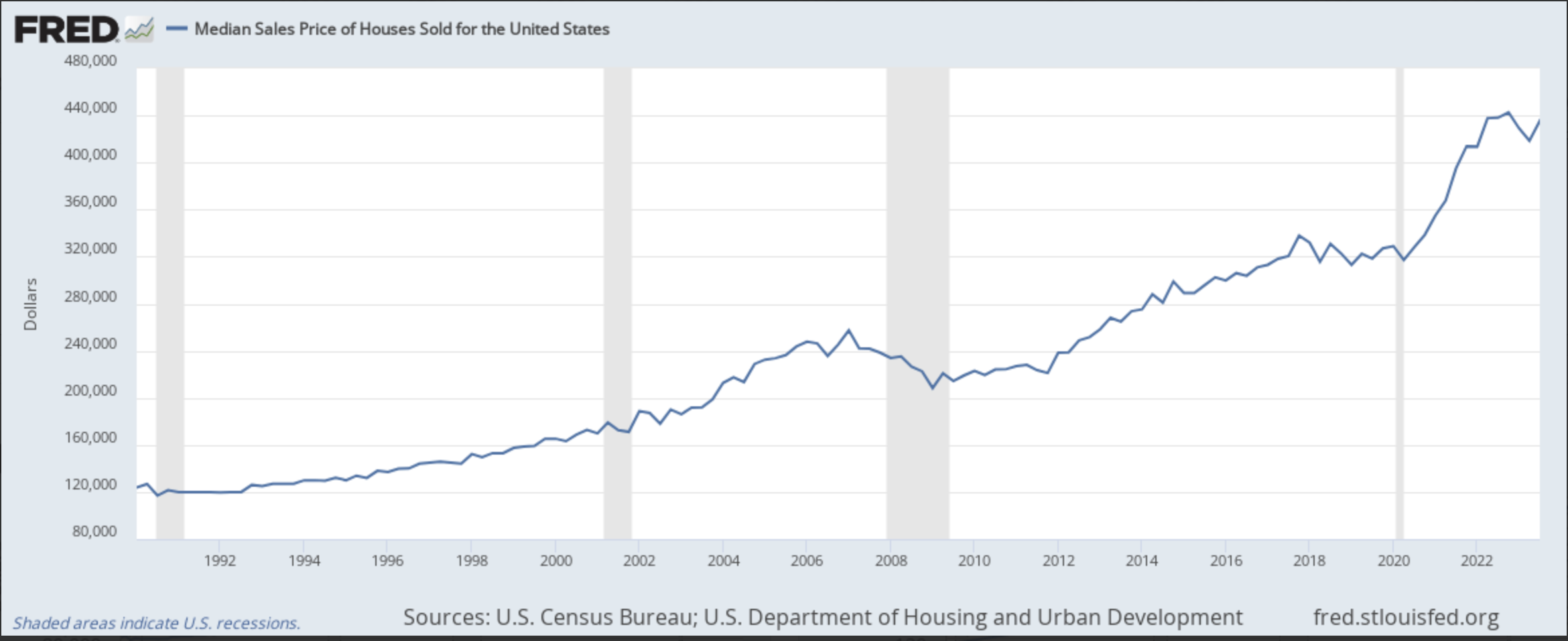

Census data showing a steady then sharper rise in housing prices in the United States

The consensus answer from economists, policy makers, housing industry affiliates and well, myself is that we should build more homes. The thinking is simple. Housing follows supply and demand. Therefore, if there is more demand than supply, prices rise. Similarly if there is more supply than demand, prices fall. Law makers should be working to make development of more homes easier and less costly.

To explain let’s use the concept of musical chairs.

When there are enough chairs for everyone, everyone finds a seat. But, when there aren’t enough chairs inevitably someone is left out. In terms of housing this could be the poor, disabled, or even just the young who didn’t come of age early enough to purchase a house at an affordable price.

When there are enough chairs for everyone, everyone finds a seat. But, when there aren’t enough chairs inevitably someone is left out. In terms of housing this could be the poor, disabled, or even just the young who didn’t come of age early enough to purchase a house at an affordable price.

People may push back and say “we don’t need more housing we need more affordable housing”. The problem with strictly building “affordable” housing is that making it “affordable” means subsidizing the cost of building. Someone pays for it. Either tax payers or developers. Developers will not build housing if they cannot make a profit. There’s just no way around that. We can’t make developers do work that loses them money. Local governments generally do not have the budget surplus to subsidize the amount of housing needed to address shortages either. As a result much less or no housing gets built if it needs to be “affordable”. That’s why seemingly well intentioned programs like inclusionary zoning and affordable housing mandates are counter productive to their stated goals2. By trying to ensure below market rate housing for those who need it these additional regulations reduce the overall number of units that get built.

People may push back and say “we don’t need more housing we need more affordable housing”. The problem with strictly building “affordable” housing is that making it “affordable” means subsidizing the cost of building. Someone pays for it. Either tax payers or developers. Developers will not build housing if they cannot make a profit. There’s just no way around that. We can’t make developers do work that loses them money. Local governments generally do not have the budget surplus to subsidize the amount of housing needed to address shortages either. As a result much less or no housing gets built if it needs to be “affordable”. That’s why seemingly well intentioned programs like inclusionary zoning and affordable housing mandates are counter productive to their stated goals2. By trying to ensure below market rate housing for those who need it these additional regulations reduce the overall number of units that get built.

If we can reduce the obstacles to building more housing we can successfully address this crisis. Rental and housing costs would inevitably lower due to more competition and supply. First time home owners can find desirable places to live. Retirees can downsize to smaller homes as they age out of the need for larger places. This frees up larger housing stock for those with the need or desire for more space. Homeowners enjoy lower property taxes, local governments enjoy larger and more diverse tax bases, and everyone enjoys lower cost of living.

My main motivation and goal is to ensure everyone can find an affordable place to live in their desired location. With that goal, the obvious solution to build our way to that desired outcome. Other motivations such as preserving neighborhood character, increasing home owner wealth, keeping traffic at bay, and many more rebuttals are less of a concern to me than ensuring people can reasonably afford to have a roof over their heads.

My main motivation and goal is to ensure everyone can find an affordable place to live in their desired location. With that goal, the obvious solution to build our way to that desired outcome. Other motivations such as preserving neighborhood character, increasing home owner wealth, keeping traffic at bay, and many more rebuttals are less of a concern to me than ensuring people can reasonably afford to have a roof over their heads.

FAQs

What about the character of the neighborhoods? What if we don’t want more housing where we live?

Housing follow the “tragedy of the anti-commons”. The inverse of the “tragedy of the commons.” Too many individuals or entities have the power to block a change, even if it’s in the collective interest. This leads to underuse or underdevelopment of shared resources or opportunities. If every local jurisdiction vetos housing then nothing will get built and we all suffer. That’s why I believe states should govern over issues like these. The character of the neighborhood is also not a sufficient justification for blocking other people’s ability to live in a desirable place.

A lot of people’s wealth is tied up in their homes. If we reduce housing prices then people will lose wealth!

Yes, some people will lose wealth if the value of their homes fall. Personally, I believe housing should be primarily for providing a place to live rather than an investment asset. It is a good way to encourage Americans to invest but as an investment vehicle it has many flaws. It’s not diversified, it’s not liquid, you pay perpetual taxes on it, and it encourages local NIMBYism. I could write more about this but Slow Boring has a great article on this topic The High Cost of Promoting Homeownership that I think aligns with my thinking for the most part.

Footnotes

-

The Housing Theory of Everything is a great article about this problem and how it affects so many other aspects of society. ↩

-

Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes explains this concept is a great white paper ↩